'Breaking point'

A 13 Investigates analysis of every felony case filed in Harris County since 2011 found more defendants are getting out on bond and re-offending now than in previous years.

Ted Oberg Investigates

By Ted Oberg, Sarah Rafique and Grace Manthey

HOUSTON, Texas (KTRK) -- The “I’m sorrys” weren’t cutting it anymore. Norma Johnson needed help.

She called the Houston Police Department last November, alleging her partner, Demetrus Whiting, hit her. Police arrested him and a judge eventually lowered his bail to $50,000.

Even though Johnson said she was the victim of family violence, she still bonded him out. The couple’s daughters missed their dad.

“I wanted my family together,” Johnson told 13 Investigates’ Ted Oberg. “He would tell me he was going to change and you always, in hope of that change, you risk it, especially when you love somebody. So, I bonded him out. It was good, maybe for a little while.”

November 18, 2021

There are five different categories of felonies, including capital felonies, first second and third degree felonies and state jail felonies. They are the most severe types of crimes.

Bail is a constitutional guarantee that the accused cannot be kept behind bars awaiting trial because judges don't want to let them out or because they can't afford to pay the bond amount. It isn't punishment, it's simply a way to try and get the accused to show back up for court.

Bond is the monetary amount that a defendant must pay in order to get out of jail while their case is pending. It is set by a judge.

What is a felony?

What is bail?

What is bond?

• About 27,100 defendants are currently out on a felony bond.

• Defendants in 73% of felony cases filed last year posted bond.

• In the last 10 years, 19,500 people were accused of a felony, posted bond and were arrested again for another felony before their previous case could be resolved.

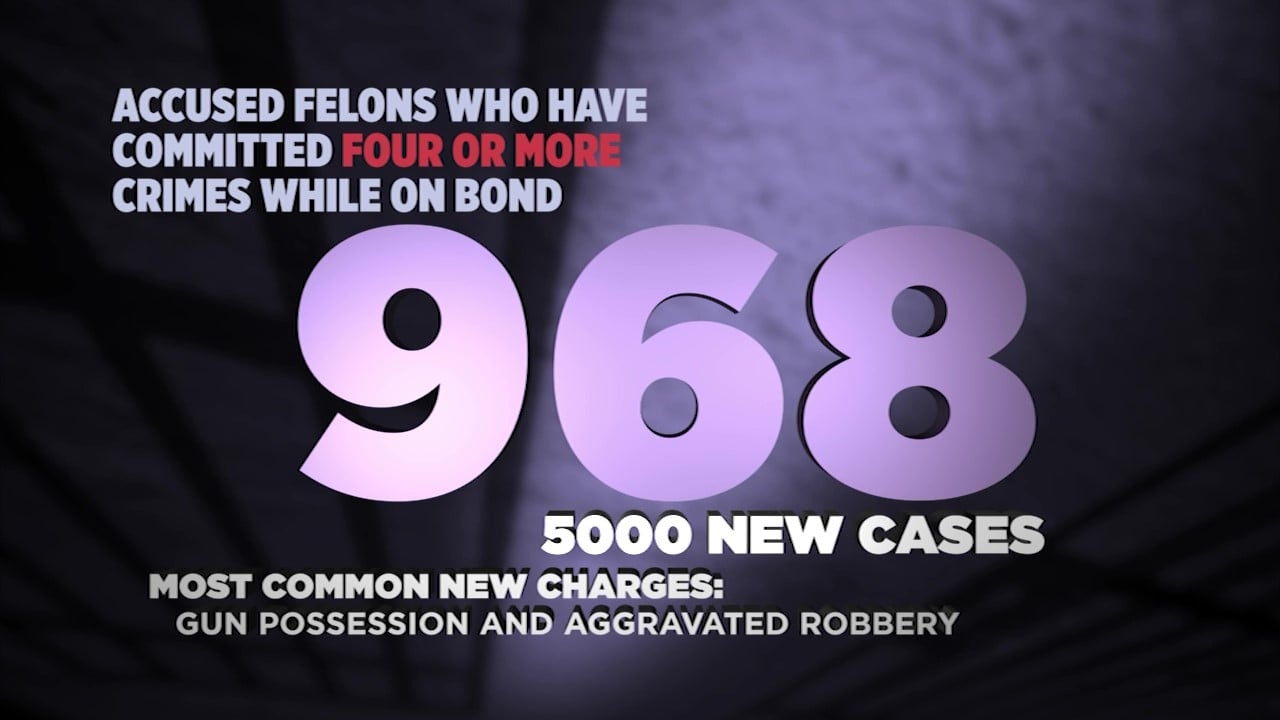

• In the last five years, 13 Investigates found 968 accused felons who allegedly committed four or more new serious crimes while out on bond.

Watch ABC13 and the Houston Chronicle's town hall on 'Houston's Rising Crime'

Click play to watch the full investigation

Despite Johnson helping to pay for him to get out of jail, Whiting ended up allegedly hurting her again. He went back to jail and got out on bond on his own.

Whiting is currently out on five felony bonds, part of a growing trend across Harris County where serious repeat offenders are getting out of jail more than in previous years as they wait for their case to work its way through the court system.

13 Investigates looked at every felony case filed in the county since 2011 and found five times as many repeat offenders got out on bond this year compared to 10 years ago.

Our analysis of data from the Harris County District Attorney’s Office found just 3.5% of cases filed in 2011 resulted in the defendant getting out on a felony bond compared to 18.8% of cases filed so far this year, where the defendant got out on bond.

They don't care. They'll go to another crime. They know they can get out. Even if someone like this guy, he bonded out, he doesn't care. It's no fear of a punishment.

Shakera Gladney, crime victim

The only Harris County judge who agreed to speak with us said judges are required by Texas law to set a reasonable bond and more judges are doing that now than in previous years.

Bonding companies say they work to make sure defendants show up to trial, but with a backlog of cases, it could be years before a case is resolved.

“When I was a prosecutor 10 years ago, judges didn't have hearings as required by the constitution to hold people on no bond. They would just hold them at no bond,” said Judge Chris Morton, of the 230th Criminal District Court.

And while those defendants are out on bond, victims like Johnson say they are tired of being re-traumatized by repeat offenders.

“I think they’re just not trying to fix the problem. They're just trying to avoid overpopulation and not help because that's what they're doing. They're not helping him,” she said. “I don't know how it's going to get fixed. All I know is that when we actually got together, I had already bonded him twice for charges that weren't related to me and he was good for a long time.”

Norma Johnson

'Innocent until proven guilty'

With deadly crimes rising in Houston, Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg said judges need to do a better job setting bail amounts for would-be repeat violent offenders.

During an ABC13 and Houston Chronicle town hall on “Houston’s Rising Crime,” Ogg said she would support a constitutional amendment that gives judges more power to hold some defendants in jail without bond.

In Texas, the judges we elect set bail for the accused. 13 Investigates reached out to all of the county’s 23 elected district court judges by email and postal mail to ask them about their process and our findings. Morton was the only judge willing to talk about the issue.

Morton said bail gives defendants an opportunity to pay to get out of jail while their case works its way through the criminal justice system. When the case is resolved, and if the defendant has not missed any court appearances, the bail money will be returned.

The amount can be as little as $1,000 for a misdemeanor or up to $1 million or more for serious crimes, like murder. Judges can also issue a personal recognizance bond, where they allow a felony defendant to get out of jail with as little as a signature and promise to appear in court.

A new law goes into effect next month that addresses “the continual release of habitual and violent offenders on multiple felony personal bonds.” The law will no longer allow defendants who are already out on bond for a violent crime to get out on a personal recognizance bond, instead requiring them to pay cash to get out.

Morton said judges rely on the widely-used Public Safety Assessment when determining what amount to set bail at. The assessment is a scoring system in the pretrial phase that factors a defendant's chances of failure to appear in court and the likelihood they will commit a new crime while on release.

13 Investigates' Ted Oberg spoke with Harris County Judge Chris Morton. He was the only district judge in the county who agreed to an interview about bond.

The only time a defendant can be held without bond is if the district attorney’s office presents enough evidence that releasing the defendant would be a danger to the community, Morton said.

He said since judges are doing a better job of following the law and giving every defendant bail, more defendants are getting out on bond.

Ogg said there has been an increase in gang violence, shootings and homicides, spurred by an increase of violent repeat offenders out on bond.

Although other communities across the U.S. are also experiencing spikes in crime, Ogg said the issue of violent repeat offenders is worse in Harris County compared to other urban areas across the state.

“(We should) stop the release of repeatedly violent people on second, third, 10th, 15th bails and that’s not just in the district courts. We’re asking our misdemeanor judges not to pre-sign bonds, not to waive through domestic violence or DWI perpetrators because they become the harbingers of those more serious crimes,” Ogg said.

‘Doesn’t make any sense’

Shakera Gladney has seen the shift in the court’s bond process firsthand. She was arrested in 2016 for possession of two ecstasy pills after her common-law husband died and she turned to drugs to cope.

She received bond, but when she broke one of the conditions, the judge revoked it and wouldn't set a new one, so she was in jail for weeks.

That doesn’t happen as much anymore.

Our investigation found in 2016, defendants in 50% of felony cases filed in Harris County posted bond. Last year, that number jumped to 73%.

Clayton Bryant is currently out on 13 separate bonds, more than anyone else in the county.

Gladney was one of Bryant’s first victims in 2013. Charging documents say Bryant slammed into Gladney’s car while he was evading arrest from police.

Bryant was accused of evading police again last year, while out on eight felony bonds for charges including aggravated assault and felon in possession of a firearm.

Gladney, who said she spent months in jail while she couldn’t get bond for a nonviolent offense, is now frustrated watching the man who victimized her get bond over and over again.

“It just still doesn't make any sense,” Gladney said. “It feels like a slap in the face.”

We reached out to Bryant’s attorney, but he didn’t return our calls.

On top of angering victims, Gladney said allowing repeat offenders to get out on multiple bonds for violent crimes sends the wrong message to the accused.

Still, Morton said despite wanting a safe community for him and his neighbors, he has to look at each defendant as “innocent until proven guilty.”

“As a human being, everyone's conflicted, but I have an ethical obligation to put that aside. I can't judge things based upon my feelings,” Morton said. “I can't judge things based upon the feelings of the community. I can't judge things based upon what's in the media. I can only judge things based upon the law. That's what I swore to do and that is my ethical obligation.”

Bondsman: 'We're the accountability'

In Harris County, about 27,100 defendants are out on felony bond, according to the district attorney’s office.

The most frequent charges for defendants who posted felony bond this year are felon in possession of a weapon, possession of a controlled substance or aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

In the last five years alone, 13 Investigates found 968 accused felons in Harris County who, like Whiting, allegedly committed four or more new serious crimes since getting out on bond.

Those repeat offenders have racked up nearly 5,000 new cases combined, each one with a victim experiencing pain or trauma.

After Johnson worked with a bonding company to help get Whiting out of jail, he had to check in with the company every week.

Defendants who cannot afford to pay their bail can go into business with a bonding company, which posts the bail amount on their behalf. The bonding company requires the defendant to pay them a portion of the bail amount, which is not refundable.

Mario Garza, whose bonding company, A Advantage Bail Bonds, is handling some of Whiting’s bonds, said he requires all of the defendants he works with to conduct weekly check-ins with him. He said the check-ins are helpful in keeping track of where defendants are and making sure they are reminded of any court appearances so they don’t miss them.

“We're the surety,” Garza said. “We’re the accountability. We're the financial accountability of a defendant.”

Garza said he typically charges 10% of the bond amount, which is nonrefundable to the defendant or whoever is paying for it on their behalf. But, some defendants cannot afford the full fee so he puts them on a payment plan.

He said he only accepts about two out of every 10 people who come to him for bonding services, depending on how much he trusts that defendant to both pay him and to show up for court.

“The stability factor is what I personally look at,” Garza said. “You don't have to be rich. I just have to know that you're not going to pick up and move tomorrow after this defendant gets out and you're going to stay at your job.”

Rodney Ellis, Harris County Commissioner for Precinct 1, said he’s concerned about bail companies that “routinely accept low percentage fees, even in cases involving violent felonies.”

He doesn’t think the cash bail system makes people safer.

Wealthy individuals can buy their way out of jail even when they are accused of repeat violent offenses.

Rodney Ellis

Harris County Commissioner for Precinct 1

“Wealthy individuals can buy their way out of jail even when they are accused of repeat violent offenses,” Ellis said during a commissioner’s meeting last week.

Johnson said when she first helped bond Whiting out, she paid $4,500 down in cash and was on a payment plan with Garza for nearly $4,500 more. Garza has been offering payment plans for years.

Although Whiting's initial bond started on a payment plan, it was paid in full before his first missed court appearance.

Now, Garza said Whiting is too much of a financial risk and a threat to the community so he wants his bond revoked so he’s not on the hook anymore. If Whiting doesn’t show up, Garza could be on the hook for the full amount of Whiting’s bond, tens of thousands of dollars.

Last month, Garza went to the courthouse hoping the judge would hear his case and surrender Whiting’s bond.

Documents Garza submitted to the courts include a text message Whiting sent to Johnson’s brother that said “F--- court” and a threat to cut off his ankle monitor.

The affidavit also said Whiting hasn’t been to an in-person check-in with the bonding company since May 7 and that the co-signers of his bond say he is now homeless.

On Oct. 28, Judge Natalia Cornelio, who is presiding over the case, accepted the bond surrender but Whiting still isn’t in custody.

We reached out to Whiting’s attorney, but he didn’t return our call.

Cornelio’s only been in office since the beginning of this year, but our investigation found defendants in 72% of cases filed in her court posted bond. It’s the highest number of defendants out on bond in the county outside of the 482nd Court, which is newly created and only recently, in October, had a judge appointed by the governor to oversee cases.

Countywide, 63% of felony cases result in a defendant posting bond compared to just 40% in 2011.

The number of defendants reoffending while out on bond is also up. Our analysis of county data found just 3.5% of felony cases were filed while the defendant was out on felony bond. This year, nearly 19% of cases that have been filed through the end of September were for defendants who were already out on at least one felony bond.

Cornelio turned down 13 Investigates’ request for an interview about bonds, saying ethics rules forbid talking to the media about it.

Morton said it’s not the bail, or monetary amount paid to get out, that protects the community, but rather the bond conditions, such as no contact with the victim, no drug or alcohol use, no committing more crimes and others. If people don’t follow the bond conditions, he said, they shouldn’t be out on bail.

‘Don’t have a crystal ball’

Countywide, there’s been an increase in crime over the years when looking at the number of cases filed. In 2011, there were 41,792 felony cases filed. Five years later, that jumped 6% percent to 44,306 cases filed in 2016. And in 2020, there were 50,518 felony cases filed, which is 21% more than a decade ago.

The rise in crime and slow-moving criminal justice process has garnered the attention of city and county leaders.

During a Harris County Commissioner’s Court meeting on Nov. 9, Precinct 2 Commissioner Adrian Garcia proposed discussing “possible action increasing transparency on the use and practices of bail bonds in Harris County criminal courts.”

He said it is imperative to bring transparency to the criminal justice process.

“It’s important for us to understand how the bail system is impacting the things we see happening in our community,” Garcia said.

Watch ABC13 and the Houston Chronicle's town hall on 'Houston's Rising Crime'

A screenshot of a text bondsman Mario Garza submitted as part of an affidavit requesting a judge revoke Whiting's bond.

Despite the increase in crime, our investigation found a majority of criminals accused of felonies do not re-offend while out on bond. In the last five years, there were 122,434 people accused of a felony and 89% of them haven’t been charged with another crime while out on bond.

Bail reform, which advocates for affordable bail for everyone, has impacted misdemeanor cases, but is not applicable to felony courts although it has seeped in nonetheless.

In one recent case, Garcia said bondsmen allowed a defendant to pay just 2% of their $500,000 bond. Now, Garcia said bondmen need to be part of the discussion when it comes to improving the system and minimizing repeat offenses.

Garza, president of the Professional Bondsmen of Harris County Association, said bondsmen haven’t been a part of the conversation in the past, but need to be.

He said bondsmen are not only trying to protect their financial interests, like receiving the money they put up for a defendant once the case is over, but some also consider the public safety risk.

He acknowledged not all bondsmen have the same interests of the public in mind, but he does consider if a defendant has an attitude or several assaults when deciding which defendants to work with.

“Bondsmen don't have a crystal ball, but what we try to do is we try to limit it within a probability,” he said. “I want my defendants to do better. I wanted them to do better because of quality of life and because I have to live in this city and I could be a victim one day.”

When Whiting stopped checking in with Garza, Johnson said she no longer recognized the angry person he became. The drug and alcohol use changed his complexion and made him age.

Whenever Johnson looked at a photo of her daughter laughing while Whiting smiled back, she choked up thinking about how much has changed since the two first met.

“I see a loving father. I see his kids happy with him,” she said. “He looks nothing like that anymore."

In February, when Whiting was charged once again with allegedly hitting Johnson, she finally had enough. She didn’t bail him out.

Now, as she waits for his cases to move through the court system while he’s out on bond, she hopes he doesn’t victimize anyone else.

“He wanted to get back with me and I told him I couldn't anymore. This time, my heart had enough,” Johnson said. “I was scared when I was with him. I was very afraid while we were together. I think that's why I stayed the longest, but I'm not scared anymore.”

Harris County commissioners discuss bail bonding practices during a meeting on Nov. 9.

As we continue investigating rising crime and bonds, we want to hear from you.

Copyright © 2021 KTRK-TV. All Rights Reserved.

• About 27,100 defendants are currently out on a felony bond.

• Defendants in 73% of felony cases filed last year posted bond.

• In the last 10 years, 19,500 people were accused of a felony, posted bond and were arrested again for another felony before their previous case could be resolved.

• In the last five years, 13 Investigates found 968 accused felons who allegedly committed four or more new serious crimes while out on bond.